By any measure, the 2002 Big Mountain Food and Supply Run was a major success. Thanks to all of you who contributed in so many ways. You came to the shows, were generous during the blanket dances, made donations of food, clothing and items for the silent auctions. You helped make things happen by renting halls and volunteering to work or perform your art. You made and shared meals and magic. You pulled together as community to work for a better world, in solidarity with people of Big Mountain, who are walking the Beauty Way for all of us.

By any measure, the 2002 Big Mountain Food and Supply Run was a major success. Thanks to all of you who contributed in so many ways. You came to the shows, were generous during the blanket dances, made donations of food, clothing and items for the silent auctions. You helped make things happen by renting halls and volunteering to work or perform your art. You made and shared meals and magic. You pulled together as community to work for a better world, in solidarity with people of Big Mountain, who are walking the Beauty Way for all of us.

Over the past three months you have raised energy and awareness while reaching out to strengthen the connection to indigenous people who are holding on to sacred land. Over $10,000 was raised and once again it multiplied like loaves and fishes. Combined with contributions and discounts from organic farmers and merchants more than 5 tons of food and supplies were distributed to about 80 families.

Organic fruits and vegetables including oranges, apples, dates, dried fruit, beets, potatoes, a variety of squash, carrots, turnips, leeks and onions. Coffee, beans, rice, blue corn meal, Blue Bird flour, tea, herbs, spices, incense cedar from Oregon and a whole lot of love were in packed into huge boxes for distribution. There was more than a ton of dog food, 13 cords of dry, split wood and several chain saw crews were out getting even more. We were able to leave $2500 cash behind to repair the homes of a few elders.

It was the biggest work crew in ten years and everyone was riding a high vibe. Three busses anchored a wonderful camp- the Big Purple Bus with the Clan Dyken crew, Tom’s San Juan Ridge Runner and the Bio-diesel Express from Arcata,- which was packed with a most enthusiastic North Coast crew, under the direction of the esteemed Deacon Rivers of the Elvis Underground. They kicked in $2000, four chains saws, a generator and all kinds of upbeat mojo. Other contributions included a 1000 gallon water tank, assorted building materials, warm clothes, and of course songs and stories around the fire in the evenings.

This sacred land brings out the best in the people who go there to work on it. The efforts of a small group made a difference, for the people on the land and for each other.

This sacred land brings out the best in the people who go there to work on it. The efforts of a small group made a difference, for the people on the land and for each other.

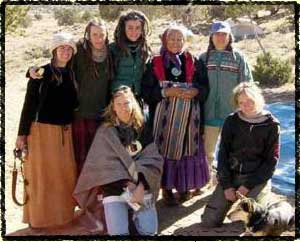

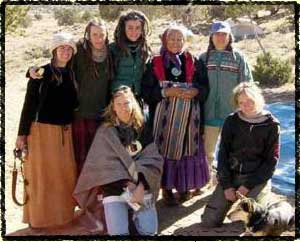

On Friday morning after Thanksgiving, we gathered for a morning circle. Most of the food had been distributed and many chores completed. People gave thanks, shared thoughts, songs and stories. During one song I went from face to face around that circle, moving my gaze from one set of eyes to the next with each shake of the rattle. I counted 51 faces in that circle, from babies to elders, men and women of the four sacred colors – red, yellow, black and white- were all represented there. It was a beautiful site, so easy to see and feel the emotion of the moment -love and unity in action.

We heard from Louise, John, Leonard and Kee Benally, siblings who grew up in the area we were camping on. They thanked us for coming, told of some of the hardship they are facing, talked of being on the land without parents or grandparents anymore. They spoke so eloquently -of lost loved ones and the struggle to keep their culture. Of dismantled wind mills, livestock impoundment and the fierce determination to hold on.

Then two members of the Arcata crew stepped forward with gifts they were sent with from the Yurok elders of Northern California. There were blankets, an elk hide, rattles, and cedar sent from the Yurok to the Dine’ and the Benally family in attendance accepted them with grace.

It was Elvira who brought us all to tears. She is one of the Aunties who comes to the camp while we are there and makes sure everything goes along smoothly. In a shaky, but clear voice she told the circle she wanted to thank each and every one of us for coming. She said this food drive means a lot to all the people here.

"It’s a way of knowing that we are not forgotten." She said as her eyes swelled with tears. "You give so much and I have nothing to give you back."

It is of course sad to be reminded of the conditions the people of Big Mountain live under, but even sadder to hear that Elvira wouldn’t know how much she has given all of us.

Later that day one of the work crews dug out some of the old water holes in the wash behind Louise’s hogan. Water used to seep into the holes from the ground as well as collect there after a rain. It has been a drought for more than two years and the holes are filling in with sand. Combine that with the coal mine using over a billion gallons of water a year to move coal and you can understand why water is harder and harder to find. Later that night and into the following morning we were blessed with the first rain in a long time. Louise said it was a female rain- soft, gentle and nurturing- activated by the attention paid to the water spots. It was a hopeful sign for the future.

What of the future? Why do the people hang on? How could they possibly win? What are the chances for survival of the traditional Dine’ people and culture? There is hope and there are concerns.

Let’s start with hope. Southern California Edison is a 59% owner, as well as the operator of the Mohave Generating Station in Laughlin, Nevada. Coal from the Black Mesa Mine, which is operated by Peabody Coal, is mixed with water from the Black Mesa aquifer and slurried through a large pipe to reach the plant, some 275 miles away. When it arrives in Laughlin, the water is turned to steam and the coal is burned to make power for Southern California. The Navajo and Hopi tribes are saying they no longer want the water to be used in this way. Very wasteful and dirty. This has caused SCE to consider the coal supply unstable and no new way of transporting it has been presented. As part of their contract to operate the plant SCE agreed to make over 58 million dollars in air pollution control improvements to the plant in 1999. To date none of that work has been done. The expense of the pollution control improvements, which would also require a six to twelve month shut down to install, combined with the uncertainty of the coal supply has caused SCE to say it may close the plant in 2005, which would effectively shut down the mine. That would be very good news for the resistance. The mine is the reason people are being relocated. We have the window of opportunity to lobby SCE and the California Public Utilities Commission to follow through on plans to close the Mohave plant, which has been labeled as the "…biggest uncontrolled source of sulfur dioxide in the Southwest-a prime contributor to the gaseous haze that clouds visibility over the Grand Canyon." (LA Times).

Now is the time, especially for people who live in California to call the PUC and let them know we want clean energy from sustainable sources. Let them know you don’t want power from the Mohave Generating Station. You can read more about the PUC and the decision to close the plant at www.cpuc.ca.gov , use the search feature on the site to find Mohave Generating Station. You can call them at 1-866-849-8390 in San Francisco or 1-866-849-8391 in LA. You can also reach Norm Carter, a PUC advisor who is familiar with the situation at 1-213-576-7056 or public.advisor.la@cpuc.ca.gov . When I spoke with him he was very open to hearing from people and told me that written or email comments have the same weight as testimony in a public hearing. Send email with Mohave Generating Station in the subject line and your views will be passed on to the commissioners who will make the decision to either spend the money and keep the plant running or close it. Time is of the essence, as this decision needs to be made soon. Let them know California can do better with renewable, clean energy that doesn’t destroy the environment and the lives of the people at Big Mountain/Black Mesa.

Of course there are plenty of people who want things to stay as they are. The mine operators are lobbying for a relax of the environmental regulations and the people who make money on this operation, from the corporate heads down to the miners and plant workers are crying about the loss of jobs and income. They pack public hearings, hire the lobbyists and have methods of influence we can only imagine. That’s why each of us is important, we have the numbers, we just need to express ourselves. There are other jobs, better investments, cleaner sources of power and more at stake then the profits of these companies. If this plant could be closed it would be a sign that thirty years of resistance to forced relocation has not been in vain.

Then it would be time to focus on the lives of the people who live here. The hardships are mounting and taking a toll.

More elders are passing on or moving away with no one to look after them or learn from them. Less and less children are using the native tongue. There is alcoholism, drug abuse and violence. Health care is minimal at best, non-existent for the resistors. Fewer traditional doctors and medicine people are practicing their craft. Sacred sites and clean water wells have been destroyed.

The Grandmothers have held it all together all this time, through tremendous adversity. They kept the flame alive and continue to nourish hope for the future. They were the ones to call for the Sundance, to tend the sheep and weave the rugs. They called for our help and keep inviting us back. I think it’s because they believe in the future. If they believe, so do I. It’s a race for survival. Fortunately it’s a marathon, not a sprint.

Our work and exchange with the Dine’ is ongoing. Please check the web site www.clandyken.com to keep up with us. We have some more projects in the planning stage. Stay in touch if you want to be part of the next trip.

By any measure, the 2002 Big Mountain Food and Supply Run was a major success. Thanks to all of you who contributed in so many ways. You came to the shows, were generous during the blanket dances, made donations of food, clothing and items for the silent auctions. You helped make things happen by renting halls and volunteering to work or perform your art. You made and shared meals and magic. You pulled together as community to work for a better world, in solidarity with people of Big Mountain, who are walking the Beauty Way for all of us.

By any measure, the 2002 Big Mountain Food and Supply Run was a major success. Thanks to all of you who contributed in so many ways. You came to the shows, were generous during the blanket dances, made donations of food, clothing and items for the silent auctions. You helped make things happen by renting halls and volunteering to work or perform your art. You made and shared meals and magic. You pulled together as community to work for a better world, in solidarity with people of Big Mountain, who are walking the Beauty Way for all of us.  This sacred land brings out the best in the people who go there to work on it. The efforts of a small group made a difference, for the people on the land and for each other.

This sacred land brings out the best in the people who go there to work on it. The efforts of a small group made a difference, for the people on the land and for each other.